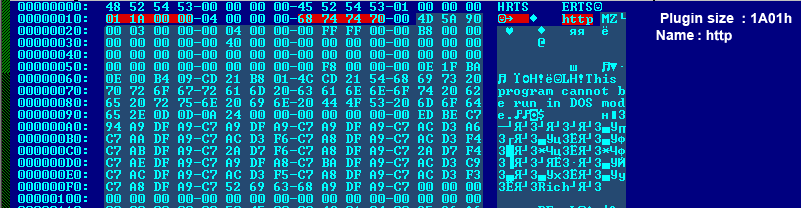

The Web lets anyone be a publisher—or a vigilante “Through our e-mails and our social media accounts we get death threats all the time,” said Janisha Gabriel. “For anyone who’s involved in this type of work, you know that you take certain risks.” These aren’t the words of a politician or a prison guard but of a Web designer. Gabriel owns Haki Creatives , a design firm that specializes in building websites for social activist groups like Black Lives Matter (BLM)—and for that work strangers want to kill her. When these people aren’t hurling threats at the site’s designer, they’re hurling attacks at the BLM site itself—on 117 separate occasions in the past six months, to be precise. They’re renting servers and wielding botnets, putting attack calls out on social media, and trialling different attack methods to see what sticks. In fact, it’s not even clear whether ‘they’ are the people publicly claiming to perform the attacks. I wanted to know just what it takes to keep a website like BlackLivesMatter.com online and how its opponents try to take it down. What I found was a story that involves Twitter campaigns, YouTube exposés, Anonymous-affiliated hacker groups, and a range of offensive and defensive software. And it’s a story taking place in the background whenever you type in the URL of a controversial site. BlackLivesMatter.com Although the Black Lives Matter movement has been active since 2013, the group’s official website was set up in late 2014 after the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Until that point, online activity had coalesced around the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag, but when the mass mobilizations in Ferguson took the movement into the public eye, a central site was created to share information and help members connect with one another. Since its creation, pushback against BLM has been strong in both the physical and digital world. The BLM website was taken down a number of times by DDoS attacks, which its original hosting provider struggled to deal with. Searching for a provider that could handle a high-risk client, BLM site admins discovered MayFirst , a radical tech collective that specializes in supporting social justice causes such as the pro-Palestinian BDS movement, which has similarly been a target for cyberattacks . MayFirst refers many high-profile clients to eQualit.ie , a Canadian not-for-profit organization that gives digital support to civil society and human rights groups; the group’s Deflect service currently provides distributed denial of service (DDoS) protection to the Black Lives Matter site. In a report published today , eQualit.ie has analyzed six months’ worth of attempted attacks on BLM, including a complete timeline, attack vectors, and their effectiveness, providing a glimpse behind the curtain at what it takes to keep such a site running. The first real attack came only days after BLM signed up with Deflect. The attacker used Slowloris , a clever but dated piece of software that can, in theory, allow a single machine to take down a Web server with a stealthy but insistent attack. Billed as “the low bandwidth yet greedy and poisonous http client,” Slowloris stages a “slow” denial of service attack. Instead of aggressively flooding the network, the program makes a steadily increasing number of HTTP requests but never completes them. Instead, it sends occasional HTTP headers to keep the connections open until the server has used up its resource pool and cannot accept new requests from other legitimate sources. Elegant as Slowloris was when written in 2009, many servers now implement rules to address such attacks. In this case, the attack on BLM was quickly detected and blocked. But the range of attack attempts was about to get much wider. Anonymous “exposes racism” On May 2, 2016, YouTube channel @anonymous_exposes_racism uploaded a video called “ Anonymous exposes anti-white racism . ” The channel, active from eight months before this date, had previously featured short news clips and archival footage captioned with inflammatory statements (“Louis Farrakhan said WHITE PEOPLE DESERVE TO DIE”). But this new video was original material, produced with the familiar Anonymous aesthetic—dramatic opening music, a masked man glitching across the screen, and a computerized voice speaking in a strange cadence: “We have taken down a couple of your websites and will continue to take down, deface, and harvest your databases until your leaders step up and discourage racist and hateful behavior. Very simply, we expect nothing less than a statement from your leadership that all hate is wrong… If this does not happen we will consider you another hate group and you can expect our attention.” The “we” in question was presumably a splinter cell of Anonymous known as the Ghost Squad Hackers. Three days previously, in a series of tweets on April 29, Ghost Sqaud’s self-styled admin “@_s1ege” claimed to have taken the BLM site offline. Ghost Squad had a history of similar claims; shortly before this, it had launched an attack against a Ku Klux Klan website , taking it offline for a period of days. Dr. Gabriella Coleman is an anthropologist and the author of Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy — considered the foremost piece of scholarship on Anonymous. (She also serves as a board member of eQualit.ie.) She said that Ghost Squad is currently one of the most prolific defacement and DDoS groups operating under the banner of Anonymous, but she also noted that only a few members have ever spoken publicly. “Unless you’re in conversation with members of a group, it’s hard to know what their culture is,” said Coleman. “I could imagine hypothetically that a lot of people who use the Ghost Squad mantle might not be for [attacking Black Lives Matter] but also might not be against it enough to speak out. You don’t know whether they all actively support it or just tolerate it.” Just as with Anonymous as a whole, this uncertainty is compounded by doubts about the identity of those claiming to be Ghost Squad at any given time—a fact borne out by the sometimes chaotic attack patterns shown in the traffic analytics. The April 29 attack announced by S1ege was accompanied by a screenshot showing a Kali Linux desktop running a piece of software called Black Horizon. As eQualit.ie’s report notes, BlackHorizon is essentially a re-branded clone of GoldenEye , itself based on HULK , which was written as proof-of-concept code in 2012 by security researcher Barry Shteiman. All of these attack scripts share a method known as randomized no-cache flood, the concept of which is to have one user submit a high number of requests made to look like they are each unique. This is achieved by choosing a random user agent from a list, forging a fake referrer, and generating custom URL parameter names for each site request. This tricks the server into thinking it must return a new page each time instead of serving up a cached copy, maximizing server load with minimum effort from the attacker. But once details of the Ghost Squad attack were published on HackRead , a flurry of other attacks materialized, many using far less effective methods. (At its most basic, one attack could be written in just three lines of Python code.) Coleman told me that this pattern is typical. “DDoS operations can attract a lot of people just to show up,” she said. “There’ll always be a percentage of people who are motivated by political beliefs, but others are just messing around and trying out whatever firepower they have.” One group had first called for the attack, but a digital mob soon took over. Complex threats Civil society organizations face cyberattacks more often than most of us realize. It’s a problem that these attacks exist in the first place, of course, but it’s also a problem that both successful and failed attempts so often happen in silence. In an article on state-sponsored hacking of human rights organizations, Eva Galperin and Morgan Marquis-Boire write that this silence only helps the attackers . Without publicly available information about the nature of the threat, vulnerable users lack the information needed to take appropriate steps to protect themselves, and conversations around effective defensive procedures remain siloed. When I spoke to Galperin, who works as a global policy analyst at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, she said that she hears of a civil society group being attacked “once every few days,” though some groups draw more fire and from a greater range of adversaries. “[BLM’s] concerns are actually rather complicated, because their potential attackers are not necessarily state actors,” said Galperin. “In some ways, an attacker that is not a nation state—and that has a grudge—is much more dangerous. You will have a much harder time predicting what they are going to do, and they are likely to be very persistent. And that makes them harder to protect against.” By way of illustration, Galperin points to an incident in June 2016 when prominent BLM activist Deray Mckesson’s Twitter account was compromised despite being protected by two-factor authentication. The hackers used social engineering techniques to trick Mckesson’s phone provider into rerouting his text messages to a different SIM card , an attack that required a careful study of the target to execute. Besides their unpredictability, persistence was also a defining feature of the BLM attacks. From April to October of this year, eQualit.ie observed more than 100 separate incidents, most of which used freely available tools that have documentation and even tutorials online. With such a diversity of threats, could it ever be possible to know who was really behind them? Chasing botherders One morning soon after I had started researching this story, a message popped up in my inbox: “Hello how are you? How would you like to prove I am me?” I had put the word out among contacts in the hacking scene that I was trying to get a line on S1ege, and someone had reached out in response. Of course, asking a hacker to prove his or her identity doesn’t get you a signed passport photo; but whoever contacted me then sent a message from the @GhostSquadHack Twitter account, used to announce most of the team’s exploits, a proof that seemed good enough to take provisionally. According to S1ege, nearly all of the attacks against BLM were carried out by Ghost Squad Hackers on the grounds that Black Lives Matter are “fighting racism with racism” and “going about things in the wrong way.” Our conversation was peppered with standard-issue Anon claims: the real struggle was between rich and poor with the media used as a tool to sow division and, therefore, the real problem wasn’t racism but who funded the media. Was this all true? It’s hard to know. S1ege’s claim that Ghost Squad was responsible for most of the attacks on BLM appears to be new; besides the tweets on April 29, none of the other attacks on BLM have been claimed by Ghost Squad or anyone else. To add more confusion, April 29 was also the date that S1ege’s Twitter account was created, and the claim to be staging Op AllLivesMatter wasn’t repeated by the main Ghost Squad account until other media began reporting it, at which point the account simply shared posts already attributing it to them. Despite being pressed, S1ege would not be drawn on any of the technical details which would have proved inside knowledge of the larger attacks. Our conversation stalled. The last message before silence simply read: “The operation is dormant until we see something racist from their movement again.” Behind the mask As eQualit.ie makes clear, the most powerful attacks leveraged against the BLM website were not part of the wave announced back in April by Ghost Squad. In May, July, September, and October, a “sophisticated actor” used a method known as WordPress pingback reflection to launch several powerful attacks on the site, the largest of which made upwards of 34 million connections. The attack exploits an innocuous feature of WordPress sites, their ability to send a notification to another site that has been linked to, informing it of the link. The problem is that, by default, all WordPress sites can be sent a request by a third party, which causes them to give a pingback notification to any URL specified in the request. Thus, a malicious attacker can direct hundreds of thousands of legitimate sites to make requests to the same server, causing it to crash. Since this attack became commonplace, the latest version of WordPress includes the IP address requesting the pingback in the request itself. Here’s an example: WordPress/4.6; http://victim.site.com; verifying pingback from 8.8.4.4 Sometimes these IP addresses are spoofed—for illustration purposes, the above example (8.8.4.4) corresponds to Google’s public DNS server—but when they do correspond to an address in the global IP space, they can provide useful clues about the attacker. Such addresses often resolve to “botherder” machines, command and control servers used to direct such mass attacks through compromised computers (the “botnet”) around the globe. In this case, the attack did come with clues: five IP addresses accounted for the majority of all botherder servers seen in the logs. All five were traceable back to DMZHOST , an “offshore” hosting provider claiming to operate from a “secured Netherland datacenter privacy bunker.” The same IP addresses have been linked by other organizations to separate botnet attacks targeting other groups. Beyond this the owner is, for now, unknown. (The host’s privacy policy simply reads: “DMZHOST does not store any information / log about user activity.”) The eQualit.ie report mentions these details in a section titled “Maskirovka,” the Russian word for military deception, because hacking groups like Ghost Squad (and Anonymous as a whole) can also provide an ideal screen for other actors, including nation-states. Like terrorism or guerrilla combat, DDoS attacks and other online harassment fit into a classic paradigm of asymmetrical warfare, where the resources needed to mount an attack are far less than those needed to defend against it. Botnets can be rented on-demand for around $60 per day on the black market, but the price of being flooded by one can run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. (Commercial DDoS protection can itself cost hundreds of dollars per month. eQualit.ie provides its service to clients for free, but this is only possible by covering the operating costs with grant funding.) The Internet had long been lauded as a democratizing force where anyone can become a publisher. But today, the cost of free speech can be directly tied to the cost of fighting off the attacks that would silence it. Source: http://arstechnica.com/security/2016/12/hack_attacks_on_black_lives_matter/

Read the article:

The DDoS vigilantes trying to silence Black Lives Matter