When he woke up the morning of October 21, 2016, Nick Rockwell did the same thing he had done first thing every morning since The New York Times hired him as CTO: he opened The Times’ app on his phone. Nothing loaded. The app was down along with BBC, CNN, Fox News, The Guardian, and a long list of other web services, taken out by the largest DDoS attack in history of the internet. An army of infected IP cameras, DVRs, modems, and other connected devices – the Mirai botnet – had flooded servers of the DNS registrar Dyn in 17 data centers, halting a huge number of internet services that depended on it for letting their users’ computers know how to find them online. The outage had started only about five minutes before Rockwell saw the blank screen on his phone. His team kicked off a standard process that was in place for such outages, failing over to the Times’ internal DNS hosted in two of its four data centers in the US. The mobile app and the main site were back online about 45 minutes after they had gone down. While going through the fairly routine recovery process, however, something was really worrying Rockwell. The thing was, he didn’t know whether the attack was directed at many targets or at the Times specifically. If it was the latter, the effect could be catastrophic; its internal DNS wouldn’t hold against a major DDoS for more than five seconds. “It would’ve been incredibly easy to DDoS our infrastructure,” he said in a phone interview with Data Center Knowledge. His team had been a few months deep into fixing the vulnerability, but they weren’t finished. “We were OK [in the end], but we were vulnerable during that time.” The process to fix it started as they were preparing for the 2016 presidential election. Election night is the biggest event for every major news outlet, and Rockwell was determined to avoid the 2012 election night fiasco, when the site went down, unable to handle the spike in traffic. One of the steps the team decided to do in preparation for November 2016 was to fully integrate a CDN (Content Delivery Network). CDN services, such as Akamai, CloudFlare, or CDN services by cloud providers Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, store their clients’ most popular content in data centers close to where many of their end users are located – so-called edge data centers — from where “last-mile” internet service providers deliver that content to its final destinations. A CDN essentially becomes a highly distributed extension of your network, adding to it compute, storage, and bandwidth capacity in many metros around the world. That a CDN had not been integrated into the organization’s infrastructure came as a big surprise to Rockwell, who joined in 2015, after 10 months as CTO at another big publisher, Condé Nast. While at Condé Nast, he switched the publisher from a major CDN provider to a lesser-known CDN by a company called Fastly. He has since become an unapologetically big fan of the San Francisco-based startup, which now also delivers content to The New York Times users around the world. Being highly distributed by design puts CDNs in good position to help their customers handle big traffic spikes, be it legitimate traffic generated by a big news event or a malicious DDoS attack. (Rockwell said he did wonder, as the Dyn attack was unfolding, whether it was a rehearsal for election night.) Fastly ensured that on the night Donald Trump beat Hillary Clinton, the Times rolled without incident through a traffic spike of unprecedented size for the publisher: an 8,371 percent increase in the number of people visiting the site simultaneously, according to the CTO. The CDN has also mostly absorbed the much higher levels of day-to-day traffic The Times has seen since the election as it covers the Trump administration. The six-year-old startup, which this year crossed the $100 million annualized revenue run-rate threshold, designed its platform to give users a detailed picture of the way their traffic flows through its CDN and lots of control. Artur Bergman, Fastly’s founder and CEO, said the platform enables a user to treat the edge of their network the same way they treat their own data centers or cloud infrastructure. In your own data center you have full control of your tools for improving your network’s security and performance (things like firewalls and load balancers), Bergman explained in an interview with Data Center Knowledge. While you maintain that level of control in the public cloud, you don’t necessarily have it at the edge, he said. Traditionally, CDNs have offered customers little visibility into their infrastructure, so even differentiating between a legitimate traffic spike and a DDoS attack has been hard to do quickly. Fastly gives users log access in real-time so they can see exactly what is happening to their edge nodes and make critical decisions quickly. The startup today unveiled an edge cloud platform, designed to enable developers to deploy code in edge data centers instantly, without having to worry about scaling their edge infrastructure as their applications grow. It also announced a collaboration with Google Cloud Platform, pairing its platform with the giant’s enterprise cloud infrastructure services around the world. GCP is one of two cloud providers The New York Times is using. The other one is Amazon Web Services. Today, the publisher’s infrastructure consists of three leased data centers in Newark, Boston, and Seattle, and one facility it owns and operates on its own, located in the New York Times building in Times Square, Rockwell said. The company uses a virtual private cloud by AWS and some of its public cloud services in addition to running some applications in the Google Cloud. This setup is not staying for long, however. Rockwell’s team is working to shut down the three leased data centers, moving most of its workloads onto GCP and AWS, with Fastly managing content delivery at the edge. Google’s cloud is also going to play a much bigger role than it does today. The plan is to run apps that depend on Oracle databases in AWS, while everything else, save for a few exceptions (primarily packaged enterprise IT apps), will run in app containers on GCP, orchestrated by Kubernetes. As he works to sort out what he in a conference presentation referred to as the “jumbled mess” that is The Times’ current infrastructure, Rockwell no longer worries about DDoS attacks. Luckily for his team, there was no major DDoS attack on The Times between the day he came on board and the day Fastly started delivering the publisher’s content to its readers. Whether there was one after Fastly was implemented is irrelevant to him. “It’s no longer something I have to think about.” Source: http://www.thewhir.com/web-hosting-news/how-the-new-york-times-handled-unprecedented-election-night-traffic-spike

View article:

How The New York Times Handled Unprecedented Election-Night Traffic Spike

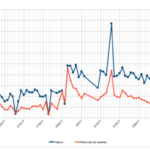

The Hajime malware is competing with the Mirai malware to enslave some IoT devices Mirai — a notorious malware that’s been enslaving IoT devices — has competition. A rival piece of programming has been infecting some of the same easy-to-hack internet-of-things products, with a resiliency that surpasses Mirai, according to security researchers. “You can almost call it Mirai on steroids,” said Marshal Webb, CTO at BackConnect, a provider of services to protect against distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks. Security researchers have dubbed the rival IoT malware Hajime, and since it was discovered more than six months ago, it’s been spreading unabated and creating a botnet. Webb estimates it’s infected about 100,000 devices across the globe. These botnets, or networks of enslaved computers, can be problematic. They’re often used to launch massive DDoS attacks that can take down websites or even disrupt the internet’s infrastructure. That’s how the Mirai malware grabbed headlines last October. A DDoS attackfrom a Mirai-created botnet targeted DNS provider Dyn, which shut down and slowed internet traffic across the U.S. Hajime was first discovered in the same month, when security researchers at Rapidity Networks were on the lookout for Mirai activity. What they found instead was something similar, but also more tenacious. Like Mirai, Hajime also scans the internet for poorly secured IoT devices like cameras, DVRs, and routers. It compromises them by trying different username and password combinations and then transferring a malicious program. However, Hajime doesn’t take orders from a command-and-control serverlike Mirai-infected devices do. Instead, it communicates over a peer-to-peernetwork built off protocols used in BitTorrent, resulting in a botnet that’s more decentralized — and harder to stop. “Hajime is much, much more advanced than Mirai,” Webb said. “It has a more effective way to do command and control.” Broadband providers have been chipping away at Mirai-created botnets, by blocking internet traffic to the command servers they communicate with. In the meantime, Hajime has continued to grow 24/7, enslaving some of the same devices. Its peer-to-peer nature means many of the infected devices can relay files or instructions to rest of the botnet, making it more resilient against any blocking efforts. Hajime infection attempts (blue) vs Mirai infection attempts (red), according to a honeypot from security researcher Vesselin Bontchev. Who’s behind Hajime? Security researchers aren’t sure. Strangely, they haven’t observed the Hajime botnet launching any DDoS attacks — which is good news. A botnet of Hajime’s scope is probably capable of launching a massive one similar to what Mirai has done. “There’s been no attribution. Nobody has claimed it,” said Pascal Geenens, a security researcher at security vendor Radware. However, Hajime does continue to search the internet for vulnerable devices. Geenens’ own honeypot, a system that tracks botnet activity, has been inundated with infection attempts from Hajime-controlled devices, he said. So the ultimate purpose of this botnet remains unknown. But one scenario is it’ll be used for cybercrime to launch DDoS attacks for extortion purposes or to engage in financial fraud. “It’s a big threat forming,” Geenens said. “At some point, it can be used for something dangerous.” It’s also possible Hajime might be a research project. Or in a possible twist, maybe it’s a vigilante security expert out to disrupt Mirai. So far, Hajime appears to be more widespread than Mirai, said Vesselin Bontchev, a security expert at Bulgaria’s National Laboratory of Computer Virology. However, there’s another key difference between the two malware. Hajime has been found infecting a smaller pool of IoT devices using ARM chip architecture. That contrasts from Mirai, which saw its source code publicly released in late September. Since then, copycat hackers have taken the code and upgraded the malware. Vesselin has found Mirai strains infecting IoT products that use ARM, MIPS, x86, and six other platforms. That means the clash between the two malware doesn’t completely overlap. Nevertheless, Hajime has stifled some of Mirai’s expansion. “There’s definitely an ongoing territorial conflict,” said Allison Nixon, director of security research at Flashpoint. To stop the malware, security researchers say it’s best to tackle the problem at its root, by patching the vulnerable IoT devices. But that will take time and, in other cases, it might not even be possible. Some IoT vendors have released security patches for their products to prevent malware infections, but many others have not, Nixon said. That means Hajime and Mirai will probably stick around for a long time, unless those devices are retired. “It will keep going,” Nixon said. “Even if there’s a power outage, [the malware] will just be back and re-infect the devices. It’s never going to stop.” Source: http://www.itworld.com/article/3190181/security/iot-malware-clashes-in-a-botnet-territory-battle.html

The Hajime malware is competing with the Mirai malware to enslave some IoT devices Mirai — a notorious malware that’s been enslaving IoT devices — has competition. A rival piece of programming has been infecting some of the same easy-to-hack internet-of-things products, with a resiliency that surpasses Mirai, according to security researchers. “You can almost call it Mirai on steroids,” said Marshal Webb, CTO at BackConnect, a provider of services to protect against distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks. Security researchers have dubbed the rival IoT malware Hajime, and since it was discovered more than six months ago, it’s been spreading unabated and creating a botnet. Webb estimates it’s infected about 100,000 devices across the globe. These botnets, or networks of enslaved computers, can be problematic. They’re often used to launch massive DDoS attacks that can take down websites or even disrupt the internet’s infrastructure. That’s how the Mirai malware grabbed headlines last October. A DDoS attackfrom a Mirai-created botnet targeted DNS provider Dyn, which shut down and slowed internet traffic across the U.S. Hajime was first discovered in the same month, when security researchers at Rapidity Networks were on the lookout for Mirai activity. What they found instead was something similar, but also more tenacious. Like Mirai, Hajime also scans the internet for poorly secured IoT devices like cameras, DVRs, and routers. It compromises them by trying different username and password combinations and then transferring a malicious program. However, Hajime doesn’t take orders from a command-and-control serverlike Mirai-infected devices do. Instead, it communicates over a peer-to-peernetwork built off protocols used in BitTorrent, resulting in a botnet that’s more decentralized — and harder to stop. “Hajime is much, much more advanced than Mirai,” Webb said. “It has a more effective way to do command and control.” Broadband providers have been chipping away at Mirai-created botnets, by blocking internet traffic to the command servers they communicate with. In the meantime, Hajime has continued to grow 24/7, enslaving some of the same devices. Its peer-to-peer nature means many of the infected devices can relay files or instructions to rest of the botnet, making it more resilient against any blocking efforts. Hajime infection attempts (blue) vs Mirai infection attempts (red), according to a honeypot from security researcher Vesselin Bontchev. Who’s behind Hajime? Security researchers aren’t sure. Strangely, they haven’t observed the Hajime botnet launching any DDoS attacks — which is good news. A botnet of Hajime’s scope is probably capable of launching a massive one similar to what Mirai has done. “There’s been no attribution. Nobody has claimed it,” said Pascal Geenens, a security researcher at security vendor Radware. However, Hajime does continue to search the internet for vulnerable devices. Geenens’ own honeypot, a system that tracks botnet activity, has been inundated with infection attempts from Hajime-controlled devices, he said. So the ultimate purpose of this botnet remains unknown. But one scenario is it’ll be used for cybercrime to launch DDoS attacks for extortion purposes or to engage in financial fraud. “It’s a big threat forming,” Geenens said. “At some point, it can be used for something dangerous.” It’s also possible Hajime might be a research project. Or in a possible twist, maybe it’s a vigilante security expert out to disrupt Mirai. So far, Hajime appears to be more widespread than Mirai, said Vesselin Bontchev, a security expert at Bulgaria’s National Laboratory of Computer Virology. However, there’s another key difference between the two malware. Hajime has been found infecting a smaller pool of IoT devices using ARM chip architecture. That contrasts from Mirai, which saw its source code publicly released in late September. Since then, copycat hackers have taken the code and upgraded the malware. Vesselin has found Mirai strains infecting IoT products that use ARM, MIPS, x86, and six other platforms. That means the clash between the two malware doesn’t completely overlap. Nevertheless, Hajime has stifled some of Mirai’s expansion. “There’s definitely an ongoing territorial conflict,” said Allison Nixon, director of security research at Flashpoint. To stop the malware, security researchers say it’s best to tackle the problem at its root, by patching the vulnerable IoT devices. But that will take time and, in other cases, it might not even be possible. Some IoT vendors have released security patches for their products to prevent malware infections, but many others have not, Nixon said. That means Hajime and Mirai will probably stick around for a long time, unless those devices are retired. “It will keep going,” Nixon said. “Even if there’s a power outage, [the malware] will just be back and re-infect the devices. It’s never going to stop.” Source: http://www.itworld.com/article/3190181/security/iot-malware-clashes-in-a-botnet-territory-battle.html