“Brexit vote site may have been hacked” warned the headlines last week after a Commons select committee published its report into lessons learned from the EU referendum. The public administration and constitutional affairs committee (Pacac) said that the failure of the voter registration website, which suffered an outage as many people tried to sign to vote up at the last minute in 2016, “had indications of being a DDoS ‘attack’”. It said it “does not rule out the possibility that the crash may have been caused … using botnets”. In the same paragraph it mentioned Russia and China. It said it “is deeply concerned about these allegations about foreign interference”. With a general election just seven weeks away, how worried should we be about foreign interference this time round? Labour MP Paul Flynn, who sits on the Pacac, certainly thinks we should be worried – although closer inspection of the report finds that, beyond the headlines, there’s a startling lack of evidence for those particular fears. In reality, a DDoS – “distributed denial of service” – attack is the bombarding of a server with requests it can’t keep up with, causing it to fail. Not only is it not actually hacking at all, but it also looks rather similar to when a lot of people at once try to use a server that doesn’t have the capacity. Given the history of government IT projects, some might favour this more prosaic explanation of why the voter registration website went offline. And that’s just what the Cabinet Office did say: “It was due to a spike in users just before the registration deadline. There is no evidence to suggest malign intervention.” So perhaps we shouldn’t fear that kind of attack, but hacking elections takes many forms. The University of Oxford’s Internet Institute, found a huge number of Twitter bots posting pro-Leave propaganda in the run up to the EU referendum. At least, that was how it was widely reported. The actual reportreveals the researchers can’t directly identify bots – they just assume accounts that tweet a lot are automated – and admit “not all of these users or even the majority of them are bots”. But the accuracy, or inaccuracy, of the research aside, there’s a bigger issue. What the Oxford Internet Institute never says is that there’s no evidence bots tweeting actually affects how anyone votes. Bots generally follow people – we’re all used to those suggestive female avatars in our notifications feeds – but people don’t really follow bots back. So when they push out propaganda, is there anyone there to see it? Of course, en masse, those bots can affect the trending topics. But getting “#Leave” trending is not the same as controlling the messaging around it, and Twitter’s algorithm explicitly tries to mitigate against such gaming of the system. And again there’s the question: who looks at tweets via the trending topics tab anyway (except perhaps journalists looking for something to pad out a listicle)? Fake news, the last of the unholy trinity, is a harder problem. We know it exists, and we know it gets in front of many people via social media sites like Facebook. We don’t really know how much it affects people and how much people see it for what it is – but the history of untrue stories in the tabloid press on topics like migration does lend weight to the idea that fake news can influence opinion. What is and isn’t fake news is a contested field. At one end of the spectrum, mainstream publications report inaccurate stories about flights full of Romanians and Bulgarians heading for the UK. At the other, teenagers in Macedonia run pro-Trump websites where the content is pure invention. Most would agree the latter is fake news, even if not the former. But this is a different problem to DDoS attacks or bot armies. The Macedonian teens aren’t ideologically driven by wanting Trump in the White House, they’re motivated by the advertising revenue their well-shared stories can earn. Even when fake news is created for propaganda rather than profit, there’s rarely a shadowy overlord pulling the strings – and bad reporting is some distance away from hacking the election. While there’s a strong case that foreign actors have tried to influence elections in other countries – such as the DNC hack in the US – we probably don’t need to worry unduly about cyberattacks swinging the UK election. Besides: why would a foreign state bother? We’ve already got a divided country struggling with its own future without any need for outside interference. Source: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/apr/20/uk-general-election-2017-hacking-ddos-attacks-bots-fake-news

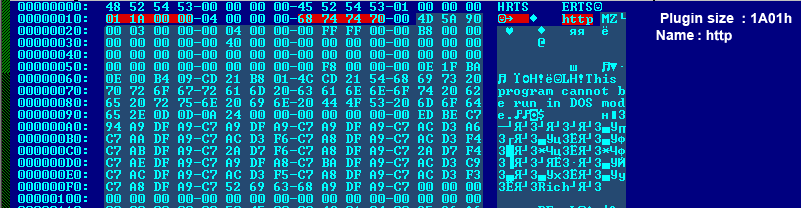

DDoSInfo – Information about DDoS and Denial of Service Attacks