“Brexit vote site may have been hacked” warned the headlines last week after a Commons select committee published its report into lessons learned from the EU referendum. The public administration and constitutional affairs committee (Pacac) said that the failure of the voter registration website, which suffered an outage as many people tried to sign to vote up at the last minute in 2016, “had indications of being a DDoS ‘attack’”. It said it “does not rule out the possibility that the crash may have been caused … using botnets”. In the same paragraph it mentioned Russia and China. It said it “is deeply concerned about these allegations about foreign interference”. With a general election just seven weeks away, how worried should we be about foreign interference this time round? Labour MP Paul Flynn, who sits on the Pacac, certainly thinks we should be worried – although closer inspection of the report finds that, beyond the headlines, there’s a startling lack of evidence for those particular fears. In reality, a DDoS – “distributed denial of service” – attack is the bombarding of a server with requests it can’t keep up with, causing it to fail. Not only is it not actually hacking at all, but it also looks rather similar to when a lot of people at once try to use a server that doesn’t have the capacity. Given the history of government IT projects, some might favour this more prosaic explanation of why the voter registration website went offline. And that’s just what the Cabinet Office did say: “It was due to a spike in users just before the registration deadline. There is no evidence to suggest malign intervention.” So perhaps we shouldn’t fear that kind of attack, but hacking elections takes many forms. The University of Oxford’s Internet Institute, found a huge number of Twitter bots posting pro-Leave propaganda in the run up to the EU referendum. At least, that was how it was widely reported. The actual reportreveals the researchers can’t directly identify bots – they just assume accounts that tweet a lot are automated – and admit “not all of these users or even the majority of them are bots”. But the accuracy, or inaccuracy, of the research aside, there’s a bigger issue. What the Oxford Internet Institute never says is that there’s no evidence bots tweeting actually affects how anyone votes. Bots generally follow people – we’re all used to those suggestive female avatars in our notifications feeds – but people don’t really follow bots back. So when they push out propaganda, is there anyone there to see it? Of course, en masse, those bots can affect the trending topics. But getting “#Leave” trending is not the same as controlling the messaging around it, and Twitter’s algorithm explicitly tries to mitigate against such gaming of the system. And again there’s the question: who looks at tweets via the trending topics tab anyway (except perhaps journalists looking for something to pad out a listicle)? Fake news, the last of the unholy trinity, is a harder problem. We know it exists, and we know it gets in front of many people via social media sites like Facebook. We don’t really know how much it affects people and how much people see it for what it is – but the history of untrue stories in the tabloid press on topics like migration does lend weight to the idea that fake news can influence opinion. What is and isn’t fake news is a contested field. At one end of the spectrum, mainstream publications report inaccurate stories about flights full of Romanians and Bulgarians heading for the UK. At the other, teenagers in Macedonia run pro-Trump websites where the content is pure invention. Most would agree the latter is fake news, even if not the former. But this is a different problem to DDoS attacks or bot armies. The Macedonian teens aren’t ideologically driven by wanting Trump in the White House, they’re motivated by the advertising revenue their well-shared stories can earn. Even when fake news is created for propaganda rather than profit, there’s rarely a shadowy overlord pulling the strings – and bad reporting is some distance away from hacking the election. While there’s a strong case that foreign actors have tried to influence elections in other countries – such as the DNC hack in the US – we probably don’t need to worry unduly about cyberattacks swinging the UK election. Besides: why would a foreign state bother? We’ve already got a divided country struggling with its own future without any need for outside interference. Source: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/apr/20/uk-general-election-2017-hacking-ddos-attacks-bots-fake-news

Category Archives: DDoS Vendors

How The New York Times Handled Unprecedented Election-Night Traffic Spike

When he woke up the morning of October 21, 2016, Nick Rockwell did the same thing he had done first thing every morning since The New York Times hired him as CTO: he opened The Times’ app on his phone. Nothing loaded. The app was down along with BBC, CNN, Fox News, The Guardian, and a long list of other web services, taken out by the largest DDoS attack in history of the internet. An army of infected IP cameras, DVRs, modems, and other connected devices – the Mirai botnet – had flooded servers of the DNS registrar Dyn in 17 data centers, halting a huge number of internet services that depended on it for letting their users’ computers know how to find them online. The outage had started only about five minutes before Rockwell saw the blank screen on his phone. His team kicked off a standard process that was in place for such outages, failing over to the Times’ internal DNS hosted in two of its four data centers in the US. The mobile app and the main site were back online about 45 minutes after they had gone down. While going through the fairly routine recovery process, however, something was really worrying Rockwell. The thing was, he didn’t know whether the attack was directed at many targets or at the Times specifically. If it was the latter, the effect could be catastrophic; its internal DNS wouldn’t hold against a major DDoS for more than five seconds. “It would’ve been incredibly easy to DDoS our infrastructure,” he said in a phone interview with Data Center Knowledge. His team had been a few months deep into fixing the vulnerability, but they weren’t finished. “We were OK [in the end], but we were vulnerable during that time.” The process to fix it started as they were preparing for the 2016 presidential election. Election night is the biggest event for every major news outlet, and Rockwell was determined to avoid the 2012 election night fiasco, when the site went down, unable to handle the spike in traffic. One of the steps the team decided to do in preparation for November 2016 was to fully integrate a CDN (Content Delivery Network). CDN services, such as Akamai, CloudFlare, or CDN services by cloud providers Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, store their clients’ most popular content in data centers close to where many of their end users are located – so-called edge data centers — from where “last-mile” internet service providers deliver that content to its final destinations. A CDN essentially becomes a highly distributed extension of your network, adding to it compute, storage, and bandwidth capacity in many metros around the world. That a CDN had not been integrated into the organization’s infrastructure came as a big surprise to Rockwell, who joined in 2015, after 10 months as CTO at another big publisher, Condé Nast. While at Condé Nast, he switched the publisher from a major CDN provider to a lesser-known CDN by a company called Fastly. He has since become an unapologetically big fan of the San Francisco-based startup, which now also delivers content to The New York Times users around the world. Being highly distributed by design puts CDNs in good position to help their customers handle big traffic spikes, be it legitimate traffic generated by a big news event or a malicious DDoS attack. (Rockwell said he did wonder, as the Dyn attack was unfolding, whether it was a rehearsal for election night.) Fastly ensured that on the night Donald Trump beat Hillary Clinton, the Times rolled without incident through a traffic spike of unprecedented size for the publisher: an 8,371 percent increase in the number of people visiting the site simultaneously, according to the CTO. The CDN has also mostly absorbed the much higher levels of day-to-day traffic The Times has seen since the election as it covers the Trump administration. The six-year-old startup, which this year crossed the $100 million annualized revenue run-rate threshold, designed its platform to give users a detailed picture of the way their traffic flows through its CDN and lots of control. Artur Bergman, Fastly’s founder and CEO, said the platform enables a user to treat the edge of their network the same way they treat their own data centers or cloud infrastructure. In your own data center you have full control of your tools for improving your network’s security and performance (things like firewalls and load balancers), Bergman explained in an interview with Data Center Knowledge. While you maintain that level of control in the public cloud, you don’t necessarily have it at the edge, he said. Traditionally, CDNs have offered customers little visibility into their infrastructure, so even differentiating between a legitimate traffic spike and a DDoS attack has been hard to do quickly. Fastly gives users log access in real-time so they can see exactly what is happening to their edge nodes and make critical decisions quickly. The startup today unveiled an edge cloud platform, designed to enable developers to deploy code in edge data centers instantly, without having to worry about scaling their edge infrastructure as their applications grow. It also announced a collaboration with Google Cloud Platform, pairing its platform with the giant’s enterprise cloud infrastructure services around the world. GCP is one of two cloud providers The New York Times is using. The other one is Amazon Web Services. Today, the publisher’s infrastructure consists of three leased data centers in Newark, Boston, and Seattle, and one facility it owns and operates on its own, located in the New York Times building in Times Square, Rockwell said. The company uses a virtual private cloud by AWS and some of its public cloud services in addition to running some applications in the Google Cloud. This setup is not staying for long, however. Rockwell’s team is working to shut down the three leased data centers, moving most of its workloads onto GCP and AWS, with Fastly managing content delivery at the edge. Google’s cloud is also going to play a much bigger role than it does today. The plan is to run apps that depend on Oracle databases in AWS, while everything else, save for a few exceptions (primarily packaged enterprise IT apps), will run in app containers on GCP, orchestrated by Kubernetes. As he works to sort out what he in a conference presentation referred to as the “jumbled mess” that is The Times’ current infrastructure, Rockwell no longer worries about DDoS attacks. Luckily for his team, there was no major DDoS attack on The Times between the day he came on board and the day Fastly started delivering the publisher’s content to its readers. Whether there was one after Fastly was implemented is irrelevant to him. “It’s no longer something I have to think about.” Source: http://www.thewhir.com/web-hosting-news/how-the-new-york-times-handled-unprecedented-election-night-traffic-spike

View article:

How The New York Times Handled Unprecedented Election-Night Traffic Spike

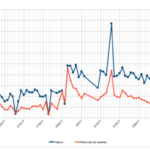

IoT malware clashes in a botnet territory battle

The Hajime malware is competing with the Mirai malware to enslave some IoT devices Mirai — a notorious malware that’s been enslaving IoT devices — has competition. A rival piece of programming has been infecting some of the same easy-to-hack internet-of-things products, with a resiliency that surpasses Mirai, according to security researchers. “You can almost call it Mirai on steroids,” said Marshal Webb, CTO at BackConnect, a provider of services to protect against distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks. Security researchers have dubbed the rival IoT malware Hajime, and since it was discovered more than six months ago, it’s been spreading unabated and creating a botnet. Webb estimates it’s infected about 100,000 devices across the globe. These botnets, or networks of enslaved computers, can be problematic. They’re often used to launch massive DDoS attacks that can take down websites or even disrupt the internet’s infrastructure. That’s how the Mirai malware grabbed headlines last October. A DDoS attackfrom a Mirai-created botnet targeted DNS provider Dyn, which shut down and slowed internet traffic across the U.S. Hajime was first discovered in the same month, when security researchers at Rapidity Networks were on the lookout for Mirai activity. What they found instead was something similar, but also more tenacious. Like Mirai, Hajime also scans the internet for poorly secured IoT devices like cameras, DVRs, and routers. It compromises them by trying different username and password combinations and then transferring a malicious program. However, Hajime doesn’t take orders from a command-and-control serverlike Mirai-infected devices do. Instead, it communicates over a peer-to-peernetwork built off protocols used in BitTorrent, resulting in a botnet that’s more decentralized — and harder to stop. “Hajime is much, much more advanced than Mirai,” Webb said. “It has a more effective way to do command and control.” Broadband providers have been chipping away at Mirai-created botnets, by blocking internet traffic to the command servers they communicate with. In the meantime, Hajime has continued to grow 24/7, enslaving some of the same devices. Its peer-to-peer nature means many of the infected devices can relay files or instructions to rest of the botnet, making it more resilient against any blocking efforts. Hajime infection attempts (blue) vs Mirai infection attempts (red), according to a honeypot from security researcher Vesselin Bontchev. Who’s behind Hajime? Security researchers aren’t sure. Strangely, they haven’t observed the Hajime botnet launching any DDoS attacks — which is good news. A botnet of Hajime’s scope is probably capable of launching a massive one similar to what Mirai has done. “There’s been no attribution. Nobody has claimed it,” said Pascal Geenens, a security researcher at security vendor Radware. However, Hajime does continue to search the internet for vulnerable devices. Geenens’ own honeypot, a system that tracks botnet activity, has been inundated with infection attempts from Hajime-controlled devices, he said. So the ultimate purpose of this botnet remains unknown. But one scenario is it’ll be used for cybercrime to launch DDoS attacks for extortion purposes or to engage in financial fraud. “It’s a big threat forming,” Geenens said. “At some point, it can be used for something dangerous.” It’s also possible Hajime might be a research project. Or in a possible twist, maybe it’s a vigilante security expert out to disrupt Mirai. So far, Hajime appears to be more widespread than Mirai, said Vesselin Bontchev, a security expert at Bulgaria’s National Laboratory of Computer Virology. However, there’s another key difference between the two malware. Hajime has been found infecting a smaller pool of IoT devices using ARM chip architecture. That contrasts from Mirai, which saw its source code publicly released in late September. Since then, copycat hackers have taken the code and upgraded the malware. Vesselin has found Mirai strains infecting IoT products that use ARM, MIPS, x86, and six other platforms. That means the clash between the two malware doesn’t completely overlap. Nevertheless, Hajime has stifled some of Mirai’s expansion. “There’s definitely an ongoing territorial conflict,” said Allison Nixon, director of security research at Flashpoint. To stop the malware, security researchers say it’s best to tackle the problem at its root, by patching the vulnerable IoT devices. But that will take time and, in other cases, it might not even be possible. Some IoT vendors have released security patches for their products to prevent malware infections, but many others have not, Nixon said. That means Hajime and Mirai will probably stick around for a long time, unless those devices are retired. “It will keep going,” Nixon said. “Even if there’s a power outage, [the malware] will just be back and re-infect the devices. It’s never going to stop.” Source: http://www.itworld.com/article/3190181/security/iot-malware-clashes-in-a-botnet-territory-battle.html

The Hajime malware is competing with the Mirai malware to enslave some IoT devices Mirai — a notorious malware that’s been enslaving IoT devices — has competition. A rival piece of programming has been infecting some of the same easy-to-hack internet-of-things products, with a resiliency that surpasses Mirai, according to security researchers. “You can almost call it Mirai on steroids,” said Marshal Webb, CTO at BackConnect, a provider of services to protect against distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks. Security researchers have dubbed the rival IoT malware Hajime, and since it was discovered more than six months ago, it’s been spreading unabated and creating a botnet. Webb estimates it’s infected about 100,000 devices across the globe. These botnets, or networks of enslaved computers, can be problematic. They’re often used to launch massive DDoS attacks that can take down websites or even disrupt the internet’s infrastructure. That’s how the Mirai malware grabbed headlines last October. A DDoS attackfrom a Mirai-created botnet targeted DNS provider Dyn, which shut down and slowed internet traffic across the U.S. Hajime was first discovered in the same month, when security researchers at Rapidity Networks were on the lookout for Mirai activity. What they found instead was something similar, but also more tenacious. Like Mirai, Hajime also scans the internet for poorly secured IoT devices like cameras, DVRs, and routers. It compromises them by trying different username and password combinations and then transferring a malicious program. However, Hajime doesn’t take orders from a command-and-control serverlike Mirai-infected devices do. Instead, it communicates over a peer-to-peernetwork built off protocols used in BitTorrent, resulting in a botnet that’s more decentralized — and harder to stop. “Hajime is much, much more advanced than Mirai,” Webb said. “It has a more effective way to do command and control.” Broadband providers have been chipping away at Mirai-created botnets, by blocking internet traffic to the command servers they communicate with. In the meantime, Hajime has continued to grow 24/7, enslaving some of the same devices. Its peer-to-peer nature means many of the infected devices can relay files or instructions to rest of the botnet, making it more resilient against any blocking efforts. Hajime infection attempts (blue) vs Mirai infection attempts (red), according to a honeypot from security researcher Vesselin Bontchev. Who’s behind Hajime? Security researchers aren’t sure. Strangely, they haven’t observed the Hajime botnet launching any DDoS attacks — which is good news. A botnet of Hajime’s scope is probably capable of launching a massive one similar to what Mirai has done. “There’s been no attribution. Nobody has claimed it,” said Pascal Geenens, a security researcher at security vendor Radware. However, Hajime does continue to search the internet for vulnerable devices. Geenens’ own honeypot, a system that tracks botnet activity, has been inundated with infection attempts from Hajime-controlled devices, he said. So the ultimate purpose of this botnet remains unknown. But one scenario is it’ll be used for cybercrime to launch DDoS attacks for extortion purposes or to engage in financial fraud. “It’s a big threat forming,” Geenens said. “At some point, it can be used for something dangerous.” It’s also possible Hajime might be a research project. Or in a possible twist, maybe it’s a vigilante security expert out to disrupt Mirai. So far, Hajime appears to be more widespread than Mirai, said Vesselin Bontchev, a security expert at Bulgaria’s National Laboratory of Computer Virology. However, there’s another key difference between the two malware. Hajime has been found infecting a smaller pool of IoT devices using ARM chip architecture. That contrasts from Mirai, which saw its source code publicly released in late September. Since then, copycat hackers have taken the code and upgraded the malware. Vesselin has found Mirai strains infecting IoT products that use ARM, MIPS, x86, and six other platforms. That means the clash between the two malware doesn’t completely overlap. Nevertheless, Hajime has stifled some of Mirai’s expansion. “There’s definitely an ongoing territorial conflict,” said Allison Nixon, director of security research at Flashpoint. To stop the malware, security researchers say it’s best to tackle the problem at its root, by patching the vulnerable IoT devices. But that will take time and, in other cases, it might not even be possible. Some IoT vendors have released security patches for their products to prevent malware infections, but many others have not, Nixon said. That means Hajime and Mirai will probably stick around for a long time, unless those devices are retired. “It will keep going,” Nixon said. “Even if there’s a power outage, [the malware] will just be back and re-infect the devices. It’s never going to stop.” Source: http://www.itworld.com/article/3190181/security/iot-malware-clashes-in-a-botnet-territory-battle.html

Continue reading here:

IoT malware clashes in a botnet territory battle

CLDAP reflection attacks may be the next big DDoS technique

Security researchers discovered a new reflection attack method using CLDAP that can be used to generate destructive but efficient DDoS campaigns. DDoS campaigns have been growing to enormous sizes and a new method of abusing CLDAP for reflection attacks could allow malicious actors to generate large amounts of DDoS traffic using fewer devices. Jose Arteaga and Wilber Majia, threat researchers for Akamai, identified attacks in the wild that used the Connection-less Lightweight Directory Access Protocol(CLDAP) to perform dangerous reflection attacks. “Since October 2016, Akamai has detected and mitigated a total of 50 CLDAP reflection attacks. Of those 50 attack events, 33 were single vector attacks using CLDAP reflection exclusively,” Arteaga and Majia wrote. “While the gaming industry is typically the most targeted industry for [DDoS] attacks, observed CLDAP attacks have mostly been targeting the software and technology industry along with six other industries.” The CLDAP reflection attack method was first discovered in October 2016 by Corero and at the time it was estimated to be capable of amplifying the initial response to 46 to 55 times the size, meaning far more efficient reflection attacks using fewer sources. The largest attack recorded by Akamai using CLDAP reflection as the sole vector saw one payload of 52 bytes amplified to as much as 70 times the attack data payload (3,662 bytes) and a peak bandwidth of 24Gbps and 2 million packets per second. This is much smaller than the peak bandwidths of more than 1Tbps seen with Mirai, but Jake Williams, founder of consulting firm Rendition InfoSec LLC in Augusta, Ga., said this amplification factor can allow “a user with low bandwidth [to] DDoS an organization with much higher bandwidth.” “CLDAP, like DNS DDoS, is an amplification DDoS. The attacker has relatively limited bandwidth. By sending a small message to the server and spoofing the source, the server responds to the victim with a much larger response,” Williams told SearchSecurity. “You can only effectively spoof the source of connectionless protocols, so CLDAP is obviously at risk.” Arteaga and Majia said enterprises could limit these kinds of reflection attacks fairly easily by blocking specific ports. “Similarly to many other reflection and amplification attack vectors, this is one that would not be possible if proper ingress filtering was in place,” Arteaga and Majia wrote in a blog post. “Potential hosts are discovered using internet scans, and filtering User Datagram Protocol destination port 389, to eliminate the discovery of another potential host fueling attacks.” Williams agreed that ingress filtering would help and noted that “CLDAP was officially retired from being on the IETF standards track in 2003” but enterprises using Active Directory need to be aware of the threat. “Active Directory supports CLDAP and that’s probably the biggest reason you’ll see a CLDAP server exposed to the internet,” Williams said. “Another reason might be email directory services, though I suspect that is much less common.” Source: http://searchsecurity.techtarget.com/news/450416890/CLDAP-reflection-attacks-may-be-the-next-big-DDoS-technique

Read more here:

CLDAP reflection attacks may be the next big DDoS technique

Hackers attacking WordPress sites via home routers

Administrators of sites using the popular blogging platform WordPress face a new challenge: hackers are launching coordinated brute-force attacks on the administration panels of WordPress sites via unsecured home routers, according to a report on Bleeping Computer. Once they’ve gained access, the attackers can guess the password for the page and commandeer the account. The home routers are corralled into a network which disseminates the brute-force attack to thousands of IP addresses negotiating around firewalls and blacklists, the report stated. The flaw was detected by WordFence, a firm that offers a security plugin for the WordPress platform. The campaign is exploiting security bugs in the TR-069 router management protocol to highjack devices. Attackers gain entry by sending malicious requests to a router’s 7547 port. The miscreants behind the campaign are playing it low-key to avoid detection, attempting only a few guesses at passwords for each router. While the exact size of the botnet is unknown, WordFence reported that nearly seven percent of all the brute-force attacks on WordPress sites last month arrived from home routers with port 7547 exposed to the internet. The flaw is exacerbated by the fact that most home users lack the technical know-how to limit access to their router’s 7547 port. In some cases, the devices do not allow the shuttering of the port. A more practical solution is offered by WordFence: ISPs should filter out traffic on their network coming from the public internet that is targeting port 7547. “The routers we have identified that are attacking WordPress sites are suffering from a vulnerability that has been around since 2014 when CheckPoint disclosed it,” Mark Maunder, CEO of WordFence CEO, told SC Media on Wednesday. The specific vulnerability, he pointed out, is the “misfortune cookie” vulnerability. “ISPs have known about this vulnerability for some time and they have not updated the routers that have been hacked, leaving their customers vulnerable. So, this is not a case of an attacker continuously evolving a technique to infect routers. This is a case of opportunistic infection of a large number of devices that have a severe vulnerability that has been known about for some time, but has never been patched.” There are two attacks, Maunder told SC. The first is the router that is infected through the misfortune cookie exploit. The other is the attacks his firm is seeing on WordPress sites that are originating from infected ISP routers on home networks. “The routers appear to be running a vulnerable version of Allegro RomPager version 4.07,” Maunders said. “In CheckPoint’s original 2014 disclosure of this vulnerability they specifically note that 4.07 is the worst affected version of RomPager. So there is nothing new or innovative about this exploit, it is simply going after ISP routers that have a large and easy to hit target painted on them.” The real story here, said Maunder, is that a number of large ISPs, several of them state owned, have gone a few years without patching their customer routers and their customers and the online community are now paying the price. “Customer home networks are now exposed to attackers and the online community is seeing their websites attacked. I expect we will see several large DDoS attacks originating from these routers this year.” Source: https://www.scmagazine.com/hackers-attacking-wordpress-sites-via-home-routers/article/649992/

Follow this link:

Hackers attacking WordPress sites via home routers

Canada one of sources for destructive IoT botnet

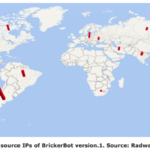

Canada is among the countries that have been stung by a mysterious botnet infecting Internet-connected devices using the Linux and BusyBox operating systems that essentially trashes the hardware, according to a security vendor. Called a Permanent Denial of Service attack (PDoS) – also called “plashing” by some – the attack exploits security flaws or misconfiguration and goes on to destroy device firmware and/or basic functions of a system, Radware said in a blog released last week. The first of two versions has rendered IoT devices affected into bricks, which presumably is why the attack has been dubbed the BrickerBot. A second version goes after IoT devices and Linux servers. “Over a four-day period, Radware’s honeypot recorded 1,895 PDoS attempts performed from several locations around the world,” the company said in the blog. “Its sole purpose was to compromise IoT devices and corrupt their storage.” After accessing a device by brute force attacks on the Telnet login, the malware issues a series of Linux commands that will lead to corrupted storage, followed by commands to disrupt Internet connectivity, device performance, and the wiping of all files on the device. Vulnerable devices have their Telnet port open. Devices tricked into spreading the attack — mainly equipment from Ubiquiti Networks Inc. including wireless access points and bridges with beam directivity — ran an older version of the Dropbear secure shell (SSH) server. Radware estimates there are over 20 million devices with Dropbear connected to the Internet now which could be leveraged for attacks. Targets include digital video cameras and recorders, which have also been victimized by the Mirai or similar IoT botnets. According to Radware, the PDoS attempts it detected came from a limited number of IP addresses in Argentina, the U.S., Canada, Russia, Iran, India, South Africa and other countries. Two versions of the bot were found starting March 20: Version one, which was short-lived and aimed at BusyBox devices, and version two, which continues and has a wider number of targets. While the IP addresses of servers used to launch the first attack can be mapped, the more random addresses of servers used in the second attack have been obscured by Tor egress nodes. The second version is not only going after IoT devices but also Unix and Linux servers by adding new commands. What makes this botnet mysterious is that it wipes out devices, rather than try to assemble them into a large dagger that can knock out web sites – like Mirai. “BrickerBot 2 is still ongoing,” Pascal Geenens, a Radware security evangelist based in Belgium, said in a phone interview this morning. “We still don’t have an idea who it is because it’s still hiding behind the Tor network.” “We still have a lot of questions like where was it originating from, what is the motivation? One of them could be someone who’s angry at IoT manufacturers for not solving that [security] problem, maybe somebody who suffered a DDoS attack and wants to get back at manufacturers by bricking the devices. That way it solves the IoT problem and gets back at manufacturers. “Another idea that I have is maybe its a hacker that is running Windows-based botnets, which are more costly to maintain.” It’s easy to inspect and compromise an IoT device through a Telnet command, he explained, so IoT botnet are easy to assemble. That lowers the cost for a botnet-for-hire. By comparison Windows devices have to be compromised through phishing campaigns that trick end users into downloading binaries that evade anti-virus software. It’s complex. So Geenens wonders if a hacker’s goal here is to get into IoT botnets and destroy the devices, which then raises the value of his Windows botnet. Another theory is the attacker is searching for Linux-based honeypots — traps set by infosec pros — with default passwords. He also pointed out Unix or Linux-based servers with default credentials are vulnerable to the BrickerBot 2 attack. However, he added, there wouldn’t be many of those because during installation process Linux ask for creation of a root password, so there isn’t a default credential. The exception, he added, is a pre-installed image downloaded from the Internet. Administrators who have these devices on their networks are urged to change factory default credentials and disable Telnet access. Network and user behavior analysis can detect anomalies in traffic, says Radware. Source: http://www.itworldcanada.com/article/canada-one-of-sources-for-destructive-iot-botnet/392242

Canada is among the countries that have been stung by a mysterious botnet infecting Internet-connected devices using the Linux and BusyBox operating systems that essentially trashes the hardware, according to a security vendor. Called a Permanent Denial of Service attack (PDoS) – also called “plashing” by some – the attack exploits security flaws or misconfiguration and goes on to destroy device firmware and/or basic functions of a system, Radware said in a blog released last week. The first of two versions has rendered IoT devices affected into bricks, which presumably is why the attack has been dubbed the BrickerBot. A second version goes after IoT devices and Linux servers. “Over a four-day period, Radware’s honeypot recorded 1,895 PDoS attempts performed from several locations around the world,” the company said in the blog. “Its sole purpose was to compromise IoT devices and corrupt their storage.” After accessing a device by brute force attacks on the Telnet login, the malware issues a series of Linux commands that will lead to corrupted storage, followed by commands to disrupt Internet connectivity, device performance, and the wiping of all files on the device. Vulnerable devices have their Telnet port open. Devices tricked into spreading the attack — mainly equipment from Ubiquiti Networks Inc. including wireless access points and bridges with beam directivity — ran an older version of the Dropbear secure shell (SSH) server. Radware estimates there are over 20 million devices with Dropbear connected to the Internet now which could be leveraged for attacks. Targets include digital video cameras and recorders, which have also been victimized by the Mirai or similar IoT botnets. According to Radware, the PDoS attempts it detected came from a limited number of IP addresses in Argentina, the U.S., Canada, Russia, Iran, India, South Africa and other countries. Two versions of the bot were found starting March 20: Version one, which was short-lived and aimed at BusyBox devices, and version two, which continues and has a wider number of targets. While the IP addresses of servers used to launch the first attack can be mapped, the more random addresses of servers used in the second attack have been obscured by Tor egress nodes. The second version is not only going after IoT devices but also Unix and Linux servers by adding new commands. What makes this botnet mysterious is that it wipes out devices, rather than try to assemble them into a large dagger that can knock out web sites – like Mirai. “BrickerBot 2 is still ongoing,” Pascal Geenens, a Radware security evangelist based in Belgium, said in a phone interview this morning. “We still don’t have an idea who it is because it’s still hiding behind the Tor network.” “We still have a lot of questions like where was it originating from, what is the motivation? One of them could be someone who’s angry at IoT manufacturers for not solving that [security] problem, maybe somebody who suffered a DDoS attack and wants to get back at manufacturers by bricking the devices. That way it solves the IoT problem and gets back at manufacturers. “Another idea that I have is maybe its a hacker that is running Windows-based botnets, which are more costly to maintain.” It’s easy to inspect and compromise an IoT device through a Telnet command, he explained, so IoT botnet are easy to assemble. That lowers the cost for a botnet-for-hire. By comparison Windows devices have to be compromised through phishing campaigns that trick end users into downloading binaries that evade anti-virus software. It’s complex. So Geenens wonders if a hacker’s goal here is to get into IoT botnets and destroy the devices, which then raises the value of his Windows botnet. Another theory is the attacker is searching for Linux-based honeypots — traps set by infosec pros — with default passwords. He also pointed out Unix or Linux-based servers with default credentials are vulnerable to the BrickerBot 2 attack. However, he added, there wouldn’t be many of those because during installation process Linux ask for creation of a root password, so there isn’t a default credential. The exception, he added, is a pre-installed image downloaded from the Internet. Administrators who have these devices on their networks are urged to change factory default credentials and disable Telnet access. Network and user behavior analysis can detect anomalies in traffic, says Radware. Source: http://www.itworldcanada.com/article/canada-one-of-sources-for-destructive-iot-botnet/392242

Read the original:

Canada one of sources for destructive IoT botnet

Russian arrested in Spain ‘over mass hacking’

Spanish police say he ran the Kelihos botnet, hacking information and installing malicious software.

See the original post:

Russian arrested in Spain ‘over mass hacking’

Russian arrested in Spain ‘over mass hacking’

Spanish police say he ran the Kelihos botnet, hacking information and installing malicious software.

See the original post:

Russian arrested in Spain ‘over mass hacking’

#OpIsrael: Anonymous hackers poised to execute ‘electronic holocaust’ cyberattacks against Israel

Hacktivists pledge to take government, military and business websites offline in annual attacks. Since 2013, hackers and internet activists affiliated with the notorious Anonymous collective have targeted digital services as part of #OpIsrael, a campaign designed to take down the websites of government, military and financial services in the country. Taking place annually on 7 April, it first started in 2013 to coincide with a Holocaust memorial service. Anonymous-linked hackers take to Twitter and YouTube to tout their cybercrime plans – which includes defacements and distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks as a retaliation against Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians. On PasteBin, a list of targets for the 2017 series of attacks has been posted, naming potential victims as the government and parliament websites. In one YouTube video, links to alleged DDoS tools had been posted. These have the ability to send surges of malicious traffic at a website domain to take it offline. “We are coming back to punish you again for your crimes in the Palestinian territories as we do every year,” a statement being circulated by Anonymous-linked accounts online pledged. The statement said the hackers’ plan is to take down servers and the websites of the government, military, banks and unspecified public institutions. “We’ll erase you from cyberspace as we have every year,” it added, continuing: “[It] will be an electronic holocaust. “Elite cyber-squadrons from around the world will decide to unite in solidarity with the Palestinian people, against Israel, as one entity to disrupt and erase Israel from cyberspace. “To the government, as we always say, expect us.” Far from being shocked at the news of the attacks, both cybersecurity experts and government officials have brushed off the aggressive rhetoric from the hacking group. It is not believed that past attacks have caused any physical damage other than website outages. Dudu Mimran, a chief technology officer at Ben-Gurion University, told The Jerusalem Post on 5 April that the attacks may actually be used as “training” for the Israelis. “From a training perspective there is always a learning lessons from this kind of event,” he said. Mimran claimed the biggest threat that may come from #OpIsrael is that it keeps government and business officials distracted from other – potentially more serious attacks. “When it makes everyone busy it gives slack to more serious attackers,” he said. Nevertheless, he added that “Israel and many other Western countries – but Israel in particular – are always under attack and ultimately concluded: “It does not elevate any serious threat on Israel.” On the morning of 7 April, Anonymous tweets mounted. “#OpIsrael has begun,” one claimed. Anonymous has been linked to numerous cyberattacks in recent years, launching campaigns on targets including US president Donald Trump, the government of Thailand and Arms supplier Armscor. The group has no known leadership and remains a loose collective of hackers. Source: http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/opisrael-anonymous-hackers-poised-execute-electronic-holocaust-cyberattacks-against-israel-1615926

View post:

#OpIsrael: Anonymous hackers poised to execute ‘electronic holocaust’ cyberattacks against Israel

20,000-bots-strong Sathurbot botnet grows by compromising WordPress sites

A 20,000-bots-strong botnet is probing WordPress sites, trying to compromise them and spread a backdoor downloader Trojan called Sathurbot as far and as wide as possible. Sathurbot: A versatile threat “Sathurbot can update itself and download and start other executables. We have seen variations of Boaxxe, Kovter and Fleercivet, but that is not necessarily an exhaustive list,” the researchers noted. Sathurbot is also a web crawler, and searches for domain names that can be probed … More ?

Original post:

20,000-bots-strong Sathurbot botnet grows by compromising WordPress sites