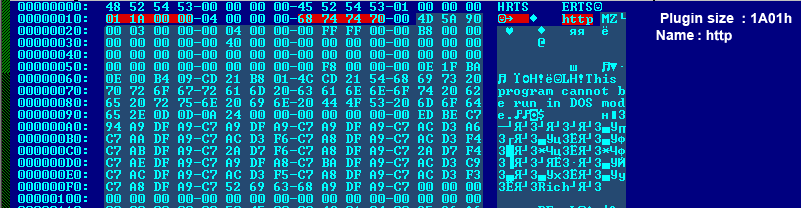

Hacktivism arrived in Singapore 10 days ago in the form of “the Messiah”, who claimed to be a member of global cyber activism group Anonymous. He threatened to unleash a legion of hackers on the country and its infrastructure if the Government did not revoke its licensing regime for news websites. Should Singaporeans be afraid? ON OCT 29, as ordinary Singaporeans went about their Tuesday, political protest took an unexpected turn. This day marked the arrival of the hacktivist in Singapore – a new breed of protester who hacks into online sites to make a point. And that day, the Singapore Government was his declared target. In a blurry YouTube video, a masked man threatened chaos on the country and its infrastructure if the licensing regime for news websites, instituted in June, was not lifted. Identifying himself as a part of cyber activism group Anonymous, he declared: “For every single time you deprive a citizen his right to information, we will cost you financial loss by aggressive cyber-intrusion.” What preceded and followed the video message were defacements of several websites, from that of the Ang Mo Kio Town Council to The Straits Times ’ blog section, by a hacker calling himself “the Messiah”. Last Saturday, when several government websites went down for several hours, some Singaporeans wondered if it was the start of the threatened chaos. Communications consultant Priscilla Wong, 36, says: “My first thought was, could this be ‘the Messiah’ carrying out his threats?” But the Infocomm Development Authority (IDA) of Singapore, the local sector regulator, told the media that it was not a case of hacking, but of scheduled maintenance that took longer than expected due to technical glitches. Then, on Wednesday, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said that the authorities would spare no effort in finding the hackers, and that they would be dealt with severely. Two days later, a page on both the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) and the Istana websites were hacked in retaliation. This move took the hostilities to a new level, say observers. “If you presume it’s the same guy or the same group, then this shows escalating tensions,” says PAP MP Zaqy Mohamad, who chairs the Government Parliamentary Committee on Information and Communications. “I suppose they took PM’s words as a challenge, and to some extent, it showed their confidence and brazenness.” How significant is this emergence of local hacktivism, and what are the ramifications? What happened? While the website defacement left many wondering if the leaking of classified personal information was just a string of codes away, cyber experts say there is a gulf between the technical skills required for the two acts, and that the two activities tend to be carried out by different groups for different purposes. Website defacements are generally considered “low-level” hacking jobs, says Paul Ducklin, a consultant at security software firm Sophos. The next level up is DDoS attacks, short for Distributed Denial of Service. In DDoS attacks, the attacker creates a network using thousands of infected computers worldwide, which are then made to overwhelm a targeted site with a huge spike in traffic. The IDA revealed on Friday that there was an unusually high level of traffic to many government websites on Nov 5, the day of the Messiah’s threatened attack, and that these indicated either attempts to scan for vulnerabilities or potential DDoS attempts. While such attacks may cause inconveniences by slowing down website access for users, they do not usually result in a loss of data or information. In the case of the PMO and Istana Web pages, the hackers exploited a vulnerability known as “cross-site scripting”, which resides in an unpatched Google search bar embedded in a Web page on each of the two government websites. Users had to type a specially crafted string of alpha-numeric search terms – understood to have been circulated on online forums – in the Google search bar before an image resembling a defaced page came on screen. IDA assistant chief executive James Kang stressed that the integrity and operations of both sites were not affected. “Data was not compromised, the site was not down and users were not affected,” he said. The most severe attacks, those resulting in personal information theft, are usually carried out in stealth by organised crime groups for financial gain, say experts. They use computer programs such as keylogging software to harvest passwords and banking account details. Foreign academics studying the Anonymous group note that the hacktivists do not have the financial wherewithal, nor desire, to perpetrate this level of cyber crime. An expert on the Anonymous collective, Gabriella Coleman of Canada’s McGill University, wrote in a recent academic paper: “It has neither the steady income nor the fiscal sponsorship to support a dedicated team tasked with recruiting individuals, coordinating activities and developing sophisticated software.” The Messiah’s actions so far seem consistent with Anonymous’ modus operandi of symbolic protest instead of real damage. “The attacks so far were mainly targeted at government-linked organisations with the purpose of creating attention, rather than causing direct damage,” says Alvin Tan, director for anti-virus software company McAfee Singapore and the Philippines. The Internet Society’s Singapore chapter president Harish Pillay emphasises that the websites that have been defaced by “the Messiah” are not high-security ones. There is no reason to link the hacking of such websites to intrusion into classified government databases, he says. “That’s like saying that since a shophouse next to Parliament House got burgled, then Parliament House is in danger of being burgled. The two are not the same.” Still, the threats have made an impact. Last Saturday, the IDA took down some of the gov.sg websites for maintenance in an attempt to patch vulnerabilities. A combination of Internet routing issues and hardware failures caused a glitch, which took the websites offline longer than expected that day, IDA said. Plugging weaknesses On Wednesday, PM Lee confirmed that the Government was beefing up its systems but cautioned that it was not possible to be “100% waterproof”, as IT systems are complicated and “somewhere or other, there will be some weakness which could be exploited”. In the wake of the hacking of the PMO and Istana pages, the IDA said that it is continuing to strengthen all government websites. This includes the checking and fixing of vulnerabilities and software patching. But bringing cyber security here up to a level that could deter elite “crackers” – the term for ill-intentioned hackers – will be challenging, say experts. A major obstacle is the lack of security experts not just in Singapore but also worldwide. Singaporean Freddy Tan, chairman of the International Information Systems Security Certification Consortium – or (ISC)2, estimates the shortfall of infocomm security staff in Singapore to be at least 400. (ISC)2 is the world’s largest not-for-profit body that educates and certifies IT security professionals. Specifically, there is a severe shortage of security analysts and digital forensics workers who monitor Internet traffic patterns, says Tan. Value of cyber protest “The Messiah” and his colleagues have heralded a new age of digital protest here. But observers are split on whether it is a valuable form of social and political activism. “It gets people to sit up and ask, what’s going on here?” notes Pillay. When it comes to the issues, the Messiah and his colleagues seem to be interested in a gamut of them. Experts say the overall agenda seems to concern equality, looking out for the underdog and a call for transparency. The lynchpin demand, made in the YouTube video on Oct 29, was directed at the Government’s licensing regime for news websites. The regulations require selected news sites with at least 50,000 unique visitors from Singapore each month over a period of two months to post a S$50,000 (RM130,000) bond and take down content against public interest or national harmony within 24 hours. It is opposed by some for what they perceive as its intent to suppress online free speech, and a group of bloggers has mounted a “Free My Internet” campaign against it. But the group has distanced itself from “the Messiah”, and among prominent online commentators a rift has emerged over whether to denounce the hacking or accept it as another form of social and political activism that could effect change in its own way. The hackers’ threats spurred some Netizens to reject this method of seeking to change policies, arguing that it amounted to one group seeking to impose its views on others rather than arguing its case. The Online Citizen, for example, said it did not condone Anonymous’ tactics, saying it did not condone “intentional violations of the law which are calculated to sabotage and disrupt Internet services which innocent third parties rely on for data”. Some have likened hacking to the civil disobedience practised by Singapore Democratic Party chief Chee Soon Juan in the 1990s, when he argued that it was just to disobey an unjust law. But if “the Messiah” wanted to add his heft to the campaign against the website licensing regime, observers were confused by his timing. After all, it was announced in June, and the outcry and public protests against it took place later that month. “Hacking Singapore sites for a law that was passed half a year ago is like laughing at a joke after everyone has left the party,” notes Professor Ang Peng Hwa, director at the Singapore Internet Research Centre. If and when the hackers are identified, the Singapore authorities are likely to bring a gamut of laws down to bear on them, say local lawyers. “At least three of Singapore’s broad laws might be invoked,” says lawyer Gilbert Leong, partner at Rodyk & Davidson. The first is the new Computer Misuse and Cybersecurity Act, passed in Parliament in January. It was called the Computer Misuse Act before but was amended to allow the Minister for Home Affairs to order a person or organisation to act against any cyber attack even before it has begun. For instance, telcos might have already been roped in to track the hacker. The second is the Criminal Law (Temporary Provisions) Act, which may be used against those who publish subversive materials that compromise public order. The third law is the Sedition Act, for exciting disaffection against the Government. Facing charges Whoever was behind the YouTube video could also face charges under the Internal Security Act for threatening the security of the Internet, says lawyer Bryan Tan, a partner in Pinsent Masons MPillay. If caught and proven guilty, “the Messiah” could face hefty fines and years in prison for his hacktivism. Law enforcers’ jobs would be made harder if “the Messiah” and his colleagues do not reside in Singapore. However, another law – the United Nations (Anti-Terrorism) Measures Regulations – might be used to extradite the offender to Singapore. This law might be used as “the Messiah” had threatened to attack Singapore’s infrastructure, which could be deemed by the authorities as a terrorist act. Whatever comes of “the Messiah” and Anonymous’ arrival in Singapore, hacktivism looks to be a new fact of life in an inter-connected, politicised society. It is however a tactic that many activists online have been quick to reject and Singaporeans on the whole have shown little interest in supporting. — The Straits Times/ANN Source: http://www.thestar.com.my/News/Regional/2013/11/10/Decoding-the-cyber-attacks.aspx

Read More:

Decoding the cyber attacks – DDoS against Singapore Government