Tensions between Japan and China are mounting following the Noda government’s decision to buy and nationalize the Senkaku Islands, and the repercussions have spilled over into cyberspace. Japan must urgently address its cybersecurity vulnerabilities and prepare for cyberthreats. Vandalism in cyberspace quickly followed the Japanese government’s announcement. China’s largest “hacktivist” group, the Honker Union of China, denounced Tokyo’s nationalization of the Senkaku Islands, calling it a declaration of war, and listed more than 100 Japanese entities as targets of a malicious campaign. For two weeks, Japanese central and local governments, banks, universities and companies experienced cyber vandalism, including the defacing of websites and distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks. According to the National Police Agency, at least eight major Japanese websites were hit with cyber-vandalism and 11 more temporarily suffered access difficulties. Websites were altered to display Chinese flags and messages stating that the Senkaku Islands belong to China. Some of the cyberattacks used Chinese IP addresses and servers, but it remains unknown who the malicious actors are or who may be supporting them. Website defacement is a comparatively unsophisticated hacking technique that makes Japan’s vulnerability to more serious and latent cyberattacks a worrying concern. Tokyo must immediately strengthen cybersecurity to decrease the gravity and impact of these threats. Most security experts believe that the chances of the Senkaku Islands dispute erupting into a military conflict are slim, given the devastating economic and political impact such an event would have. But future conflicts will most certainly involve sophisticated cyberattacks. The precedent is already well established. Three weeks prior to the outbreak of the Russia-Georgia war of 2008, Georgian websites, including those belonging to the government, financial organizations, and the media, experienced DDoS attacks, defacement and infiltration by malware designed to disrupt communications and disable servers. If such an attack took place in connection to the Senkaku dispute, it would affect both Japan and the United States. Cyberattack and espionage techniques have rapidly developed over the last four years. Malicious actors may target critical infrastructures such as power grids as well as defense networks and satellite communications. Defensive abilities would be seriously disrupted if GPS and command and control systems become unreliable. It is extremely difficult to assure timely and accurate attribution for cyberattacks. The inability to immediately retaliate after an attack and the anonymity of aggression seriously undermine any possibility of deterrence. Moreover, international cooperation is not guaranteed even where responsibility is attributable, and even where malicious actors are identified, no adequate international law prescribes the appropriate response to cyberattacks either as countries or individuals. The Ministry of Defense recently released its first cybersecurity guideline for the use of cyberspace. This document declared that under the right of self defense, the ministry is responsible for countering cyberattacks if they are launched as part of armed attacks. This interpretation of the ministry’s mission constitutes a major expansion of its previous remit, given that previously it was responsible only for the protection of internal networks and computers. Nonetheless, the document does not specify what falls under the definition of “armed attacks” and this will be determined on a case-by-case basis. This vagueness provides flexibility to deal with cyberattacks, but may also cause confusion in the government and the international community about the justification and proportionality of responses. Moreover, uncertainty exists between Tokyo and Washington as to which cyberattacks are to be regarded as “armed” for the purposes of invoking the security treaty. As long as this lack of clarity persists, the only realistic option is for Japan to reinforce its cyber defense to detect any threat, prevent or resist cyberattacks, and rapidly recover from any damage that may be incurred. To do that, Japan will also need to study cyber offenses. Joint military exercises using cyber elements would be necessary as well. Although the aforementioned guideline refers to the necessity to continue to conduct such exercises, there is no bilateral declaration about cyber exercises in the public domain. At the press conference after the U.S.-South Korea 2 + 2 meeting this year, U.S. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta suggested conducting such joint exercises to make them “more realistic.” Even if governments cannot reveal the specifics of the exercises, a joint declaration demonstrating the strong will of Tokyo and Washington would increase deterrence. Another nightmare scenario for Japan would be the spread of disinformation about the Japanese territorial claim over the Senkakus before or during a crisis situation. This could be done by hacking broadcasters, social media and other online platforms to manipulate Japanese and international audiences. An example of this occurred in the ongoing Syrian civil war. News outlets were penetrated in order to disseminate false information about the Syrian opposition and bolster support for progovernment forces. The rapid growth of social and online media leverages the proliferation of disinformation as such information is disseminated by innocent users. For example, false information could belittle the authenticity of Japanese sovereignty over the Senkakus. Disinformation could convince people that nuclear disasters are being caused by physical or cyberattacks. In a worst case scenario for Japan and the U.S., cyberattacks could cause disruption slowly or quickly, precipitating cascading shock waves through their economic, political and security systems. To counter this threat, it is essential to enhance both the intelligence capability of the government and the level of cybersecurity nationwide. The government has to establish an information-warfare strategy to build resilience to likely scenarios. It is crucial to quickly identify when and what kind of disinformation is produced. Japan also must develop methods of emergency communication for distributing accurate information to minimize manipulation as much as possible. While these grave scenarios have yet to unfold in Japan, this does not mean they will not happen as cyberthreats spread and regional uncertainty deepens. Japan must develop its cybersecurity capability now as it can ill afford the costs of further delay. Source: http://www.japantimes.co.jp/text/eo20121026a1.html

Read More:

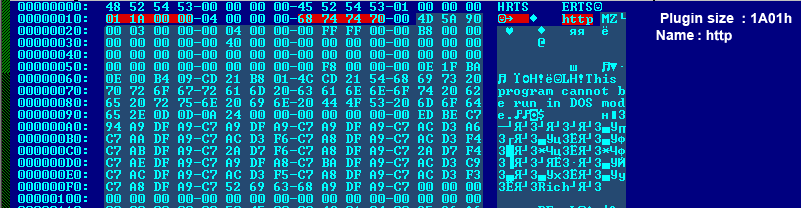

Cyber attacks on of which is Distributed Denial of Service ‘DDoS’ attack on Japanese sites