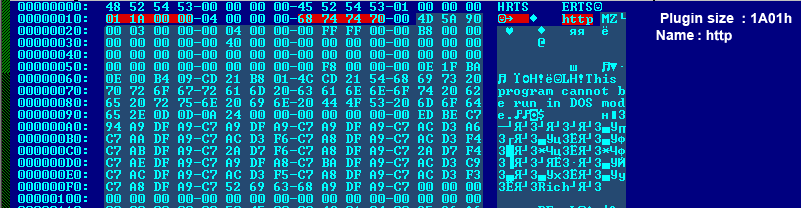

The botnets driving the recent distributed denial of service attacks are powered by millions of infected computers. Their coordinated flood of requests overwhelms the Internet’s DNS servers, slowing them down and even knocking the servers offline. The long-term solution for site operators and visitors alike may rely on reluctant ISPs working together. The risk that an Internet-connected computer is infected with malware will never be reducible to zero. It’s just the nature of software that errors happen. Where there are software-design errors, there are people who will exploit those errors to their advantage. The best PC users can hope for is to minimize the chances of an infection and to mitigate the damage a piece of malware can inflict — whether it intends to steal a user’s sensitive data or to commandeer the machine as part of a cyber attack on servers thousands of miles away. Last week, Internet users were caught in the crossfire of an online battle. On one side were spammers and other nefarious types who send malware via e-mail. On the other was the spam-fighting organization Spamhaus. As Don Reisinger reported last Wednesday, several European sites experienced significant slow-downs as a result of the attack, which may have also involved criminal gangs in Russia and Eastern Europe. In a post last Friday, Declan McCullagh explained that the technology to defeat such attacks has been known for more than a decade, although implementing the technology Internet-wide is difficult and, practically speaking, may be impossible. So where does that leave your average, everyday Internet user? Our ability to prevent our machines from being hijacked by malware will always be limited by our innate susceptibility. We’re simply too likely to be tricked into opening a file or Web page we shouldn’t. PC infection rates hold steady despite the prevalence of free antivirus software. Even the best security programs fail to spot some malware, as test results by A-V Comparatives indicate (PDF). For example, in tests conducted in August 2011, Microsoft Security Essentials was rated as Advanced (the second-highest scoring level) with a detection rate of 92.1 percent and “very few” false positives. Since we’ll never eliminate PC infections, the best defense against botnets is not at the source but rather at the point of entry to the ISP’s network. In July of last year the Internet Engineering Task Force released a draft of the Recommendations for the Remediation of Bots in ISP Networks that points out the challenges presented by bot detection and removal. Unfortunately, detecting and removing botnets isn’t much easier for ISPs. When ISPs scan their customers’ computers, the PC may perceive the scan as an attack and generate a security alert. Many people are concerned about the privacy implications of ISPs scanning the content of their customers’ machines. Then there’s the basic reluctance of ISPs to share data and work together in general. Much of the IETF’s suggested remediation comes down to educating users about the need to scan their PCs for infections and remove those they discover. While most virus infections make their presence known by slowing down the system and otherwise causing problems, the stealth nature of many bots means users may not be aware of them at all. If the bot is designed not to steal the user’s data but only to participate in a DDoS attack, users may feel no need to detect and delete the bot. One of the IETF report’s suggestions is that ISPs share “selective” data with third parties, including competitors, to facilitate traffic analysis. In March of last year the Communications Security, Reliability and Interoperability Council released its voluntary Anti-Bot Code of Conduct for ISPs (PDF). In addition to being voluntary, three of the four recommendations in the “ABCs for ISPs” rely on end users: Educate end-users of the threat posed by bots and of actions end-users can take to help prevent bot infections; Detect bot activities or obtain information, including from credible third parties, on bot infections among their end-user base; Notify end-users of suspected bot infections or help enable end-users to determine if they are potentially infected by bots; and Provide information and resources, directly or by reference to other sources, to end-users to assist them in remediating bot infections. A paper titled “Modeling Internet-Scale Policies for Cleaning up Malware” (PDF) written by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s Stephen Hofmeyr and others suggests that having large ISPs working together to analyze traffic at points of entry to their network is more effective than bot detection on end-user machines. But that doesn’t get us off the hook entirely. If every Windows PC were scanned for malware once a month, there would be far fewer bots available for the next DDoS attack. Since CNET readers tend to be more tech-savvy than average, I suggest a computer-adoption program: everyone scan two or three PCs they suspect aren’t regularly maintained by their owners (such as relatives) on a pro bono basis. Here are three steps you can take to minimize the possibility that a Windows PC will be drafted into a botnet army. Don’t use a Windows administrator account The vast majority of malware targets Windows systems. In large part it’s simply due to numbers: there are so many more installations of Windows than any other operating system that leveraging Windows maximizes a piece of malware’s effectiveness. Many people have no choice but to use Windows, most likely because their employer requires it. For many others, using an OS other than Windows is impractical. But very few people need to use a Windows administrator account on a daily basis. In the past two years I’ve used only a standard Windows account on my everyday PC, with one or two exceptions. In fact, I often forget the account lacks administrator privileges until a software installation or update requires that I enter an administrator password. Using a standard account doesn’t make your PC malware-proof, but doing so certainly adds a level of protection. Set your software to update automatically Not many years ago, experts advised PC users to wait a day or two before applying patches for Windows, media players, and other applications to ensure the patches didn’t cause more problems than they prevented. Now the risk posed by unpatched software is far greater than any potential glitches resulting from the update. In May 2011 I compared three free scanners that spot outdated, insecure software. My favorite of the three at the time was CNET’s own TechTracker for its simplicity, but now I rely on Secunia’s Personal Software Inspector, which tracks your past updates and provides an overall System Score. The default setting in Windows Update is to download and install updates automatically. Also selected by default are the options to receive recommended updates as well as those labeled important, and to update other Microsoft products automatically. Use a second anti-malware program to scan the system Since no security program detects every potential threat, it makes sense to have a second malware scanner installed for the occasional manual system scan. My two favorite manual virus-scanning programs are Malwarebytes Anti-Malware and Microsoft’s Malicious Software Removal Tool, both of which are free. I wasn’t particularly surprised when Malwarebytes found three instances of the PUP.FaceThemes virus in Registry keys of my everyday Windows 7 PC (shown below), but I didn’t expect the program to detect four different viruses in old Windows system folders on a test system with a default configuration of Windows 7 Pro (as shown on the screen at the top of this post). An unexpected benefit of the malware removal was a reduction in boot time for the Windows 7 machine from more than two minutes to just over one minute. Help for site operators who come under attack DDoS attacks are motivated primarily by financial gain, such as the incident last December that emptied a Bank of the West online account of $900,000, as Brian Krebs reported. The attacks may also be an attempt to exact revenge, which many analysts believe was implicated in last week’s DDoS onslaught against Spamhaus. The government of Iran was blamed for a recent series of DDoS attacks against U.S. banks, as the New York Times reported last January. Increasingly, botnets are being directed by political activists against their opposition, such as the wave of hacktivist attacks against banks reported by Tracy Kitten on the BankInfoSecurity.com site. While large sites such as Google and Microsoft have the resources to absorb DDoS attacks without a hiccup, independent site operators are much more vulnerable. The Electronic Frontier Foundation offers a guide for small site owners to help them cope with DDoS attacks and other threats. The Keep Your Site Alive program covers aspects to consider when choosing a Web host, backup alternatives, and site mirroring. The increasing impact of DDoS attacks is one of the topics of the 2013 Global Threat Intelligence Report released by security firm Solutionary. Downloading the report requires registration, but if you’re in a hurry, Bill Brenner offers a synopsis of the report on CSO’s Salted Hash blog. As Brenner reports, two trends identified by Solutionary are that malware is increasingly adept at avoiding detection, and Java is the favorite target of malware exploit kits, supplanting Adobe PDFs at the top of the list. The DNS server ‘vulnerability’ behind the DDoS attacks The innate openness of the Internet makes DDoS attacks possible. DNS software vendor JH Software explains how DNS’s recursion setting allows a flood of botnet requests to swamp a DNS server. CloudShield Technologies’ Patrick Lynch looks at the “open resolvers” problem from an enterprise and ISP perspective. Paul Vixie looks at the dangers of blocking DNS on the Internet Systems Consortium site. Vixie contrasts blocking with the Secure DNS proposal for proving a site’s authenticity or inauthenticity. Finally, if you’ve got two-and-a-half hours to kill, watch the interesting panel discussion held in New York City last December entitled Mitigating DDoS Attacks: Best Practices for an Evolving Threat Landscape. The panel was moderated by Public Interest Registry CEO Brian Cute and included executives from Verisign, Google, and Symantec. I was struck by one recurring theme among the panel participants: we need to educate end users, but it’s really not their fault, and also not entirely their problem. To me, it sounded more than a little bit like ISPs passing the buck. For DDoS protection click here . Source: http://howto.cnet.com/8301-11310_39-57577349-285/how-you-may-have-inadvertently-participated-in-recent-ddos-attacks/

Link:

How you may have inadvertently participated in recent DDoS attacks